The Deep Dive: Barry Lyndon at 50

On its 50 year anniversary, we take an extended look at Kubrick's painterly masterpiece, digging into the technical achievement and artistic obsession which feed into this towering adaptation of Thackeray's picaresque novel of an Irish rogue.

7/19/20256 min read

From Scoundrel to Still Life

Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon takes considerable liberties with Thackeray’s picaresque novel, which recounts the rise and fall of Redmond Barry, an Irish upstart who connives his way into the aristocracy. In Thackeray’s text, Barry is brash and boastful, narrating his own misdeeds with a wink and a shrug. Kubrick, however, replaces the unreliable first-person narration with a third-person voiceover—seemingly omniscient but often dryly ironic—creating a greater emotional and moral distance between character and audience.

This narratorial shift mirrors the visual strategy that defines the film: expansive, lingering shots, many of them zooming slowly outward, situate Barry within beautifully composed yet indifferent landscapes and interiors. Far from being a driver of his own story, Kubrick’s Barry becomes a passive figure, isolated within a world that expands around him at an often disorienting pace.

Beyond Realism: Kubrick and Thackeray in Conversation

Despite the vast differences in medium and tone, Kubrick’s film and Thackeray’s novel share an ironic sensibility. Both depict a world in which virtue is an accessory and success is largely a matter of chance. But Kubrick expands on this irony, turning Thackeray’s satirical detachment into a broader metaphysical distance.

Interestingly, Kubrick seems to channel not just Thackeray the writer, but Thackeray the illustrator. The author originally trained as an artist, and Barry Lyndon is steeped in the aesthetics of the 18th century, from Gainsborough landscapes to candlelit interiors reminiscent of de La Tour and Vermeer. Kubrick, once a photojournalist himself, was deeply attuned to the visual power of still images. His compositions echo classical painting not simply in style but in spirit: this is a film about surfaces, facades, and the historical distance that separates observer from subject.

A Fresco of Sadness

Critics have often described Barry Lyndon as slow or cold, but to do so is to miss the richness of its emotional palette. Yes, it is reserved, but deliberately so. Within its glacial pacing lies a profound meditation on time, mortality, and the smallness of human ambition. Andrew Sarris once called it “a fresco of sadness,” and the phrase holds. It’s not a melodrama, nor a tragedy in the traditional sense, but something more haunting: a story about a man who becomes a footnote in his own life.

Kubrick’s genius in Barry Lyndon lies in his refusal to editorialize. He doesn’t tell us how to feel about Barry, or Lady Lyndon, or even the moral order of the world they inhabit. Instead, he gives us space—literally and metaphorically—to watch, interpret, and reflect. In doing so, he achieves what few filmmakers have: a film that feels both intimate and monumental, historically grounded yet timelessly abstract.

Conclusion: The Beauty of Distance

In the years since its release, Barry Lyndon has undergone a remarkable critical reappraisal. Once dismissed as ponderous and self-indulgent, it is now frequently cited as one of the greatest films ever made. Its visual innovations have influenced generations of directors, from Paul Thomas Anderson to Yorgos Lanthimos. Its fusion of technical precision and thematic ambiguity continues to inspire debate and admiration.

At its heart, Barry Lyndon is a film about distance—between individuals, between ambition and outcome, between the viewer and the world onscreen. Kubrick does not ask us to love Barry. He does not ask us to hate him. He merely asks us to watch as the world expands around him, beautiful and indifferent. And in that watching, we glimpse something rare: a cinema of patience, precision, and quiet devastation.

Framing Fate: The Pictorial Distance of Barry Lyndon

When Barry Lyndon was released in 1975, Stanley Kubrick’s meticulously crafted period epic baffled audiences and divided critics. For a director whose previous films included the highly controversial A Clockwork Orange, the genre-transforming vastness of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and the war-room frenzy of Dr. Strangelove, this subdued, painterly costume drama set in 18th-century Europe seemed almost perversely still. Yet today, Barry Lyndon is widely regarded as one of Kubrick’s greatest achievements—and perhaps one of the most beautiful films ever made.

This reassessment owes much to the film’s extraordinary visual style, which critics from The Guardian to The New York Times have praised as a masterclass in cinematic composition. With every frame resembling a period painting, Kubrick’s adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray’s lesser-known novel The Memoirs of Barry Lyndon, Esq. becomes something more than a story of social climbing and moral collapse. It becomes a meditation on fate, futility, and the fragile illusion of control—all framed within one of the most exquisitely aestheticized worlds ever put to film.

Zooming Out, Letting Go

The zoom-out becomes the film’s signature visual device. In pivotal scenes, the camera slowly retreats, revealing not just the setting but the social and emotional context in which Barry is placed, suggesting a kind of cinematic fatalism. Barry is framed—quite literally—by forces beyond his control, whether in the lush green of the Irish countryside or the ornate interiors of stately homes.

A particularly revealing moment comes early in the film, when Barry’s father is killed in a duel. The shot begins in extreme long shot, the figures dwarfed by the landscape, the camera perfectly still. It’s a stark departure from the kinetic violence of most duels in cinema, and it sets the tone: death, like success or failure in Barry’s life, is absorbed by the world with hardly a ripple.

Later, as Barry rises through the ranks of society—marrying the wealthy Lady Lyndon, gambling through Europe, and dressing himself in the trappings of nobility—the zooms continue. In a trio of consecutive shots, we see Barry as a new father, then in a brothel, then Lady Lyndon seated in quiet despair. The framing remains perfect, the lighting painterly, but the emotional coherence is fractured. The zoom-out here functions as a kind of visual punctuation: moments blur, emotions drift, time slips away. Barry doesn’t so much live through these changes as he drifts through them.

A World Lit Only by Candles

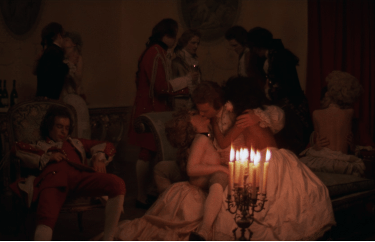

Much has been made of the technical innovation that allowed Kubrick to shoot Barry Lyndon’s candlelit scenes using a lens developed for NASA satellite photography. Kubrick retrofitted an old Mitchell BNC camera with a Zeiss 0.7f lens, capable of capturing images in extremely low light. The result? Interior scenes lit only by candles, producing soft, flattened images that enhance the illusion of 18th-century paintings brought to life.

While this technique has often been cited as a triumph of realism, it paradoxically serves to heighten the film’s artificiality. Characters glow, but they do not feel warm, as the softness of the image reinforces the sense of detachment. These are not people we are watching so much as figures posed as artistic subjects. As The Washington Post observed, it’s as though the characters are “trapped in a frame, as helpless as any portrait.”

That feeling of entrapment—of Barry as a man forever confined by the world he so desperately seeks to master—is central to the film’s thematic design. Kubrick’s world is lavish, yes, but it is also cold. Every wig and waistcoat, every gilded edge and painted wall, reminds us of the cost of Barry’s ambition. And it is a cost counted not only in money, but in empathy.

A Passive Passenger in a Fatalist Frame

What makes Barry Lyndon such an unusual film is the way it refuses to offer clear moral judgment. Thackeray’s Barry may be a rogue, but he is a likeable one. He boasts of his manipulation, but charms us with his audacity. Kubrick’s Barry, by contrast, is portrayed as a creature of circumstance—a man who begins with bold dreams and ends a sad, maimed figure, alone and bankrupt. The narration frequently undercuts the onscreen action, calling attention to Barry’s diminished agency. He doesn’t seize opportunities so much as stumble into them, often through coincidence.

This sense of passivity is mirrored by the film’s visual language. Even when Barry appears to be in control—commanding troops, seducing women, gambling with nobility—the camera reminds us of the larger world at play. It pulls away. It refuses to flinch. Kubrick’s use of scale and movement renders Barry small, even in victory.

Barry Lyndon is less about a man’s rise and fall than it is about the illusion of free will in a rigidly ordered world. The baroque settings, the endless duels and dances, the strict codes of decorum—all suggest a society obsessed with appearances and indifferent to individual suffering.

Subscribe for Film Insights

Get the latest reviews and discussions delivered monthly.

CONTACT tom.christopher.writer@gmail.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.